At first, I made these drawings because the Zapatista meeting attendees were not allowed to take photographs — something so commonplace these days.1 I came with the intent to document my encounters through drawing. As an ethnographer, I always take field notes, though I rely on a variety of methodologies and approaches in my research. In his book I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Namely My Own (2011), Michael Taussig discusses notebooks and making drawings as different types of knowing and knowledge. For me, perusing a notebook that is full of drawings, scribbles, and notes on notes, is like meandering through a landscape. Taussig, too, writes in a meandering manner in which I recognize the attempt to discuss a knowledge that is witnessing something and then keeping it vivid in drawing.

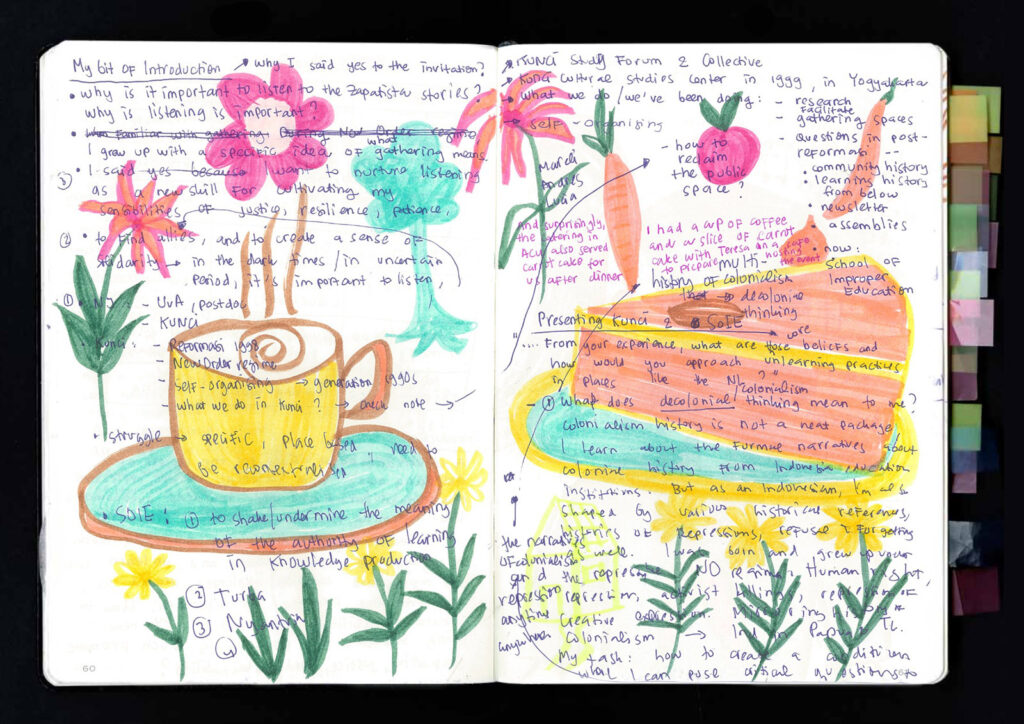

Up until recently, my knowledge of the Zapatistas came from articles, books, and films—refined products of the analyses of other thinkers, or following John van Maanen in Tales of the Field (2011), “tales” and the “translation of the understanding” of cultural analysts, filmmakers, journalists, and whomever dedicated their time to observing the Zapatista life. The Zapatista meetings presented opportunities to break this mediation. Like others there, I was able to hear the stories firsthand. But what does stories mean? A story, according to Katherine McKittrick in Dear Science and Other Stories is “an imprint of black life and the loss and the love and the rumours and the lessons and the heartbreak.”2 The Zapatistas’ stories are the imprint of oppression, which prompted me to take notes and draw. However, I can’t speak Spanish or the other languages spoken across the Tzeltal, Tzozil, Chol, Tjolobal, Zoque, Kanjobal, and Mame communities that make up the movement. I had gleaned these names from reading or watching various Zapatista-related materials. I needed the help of the translators who worked enthusiastically during the meetings in translating everything that the Zapatistas said from Spanish to English. I depended on this translation practice and embraced the lost-in-translation condition (from Spanish to English, English to Spanish, or other languages to Spanish and back again) that the process involved. On one occasion, the translation device provided by the organizer kept falling off my ear. Even during this face-to-face meeting, my encounter was mediated through translation and technology.

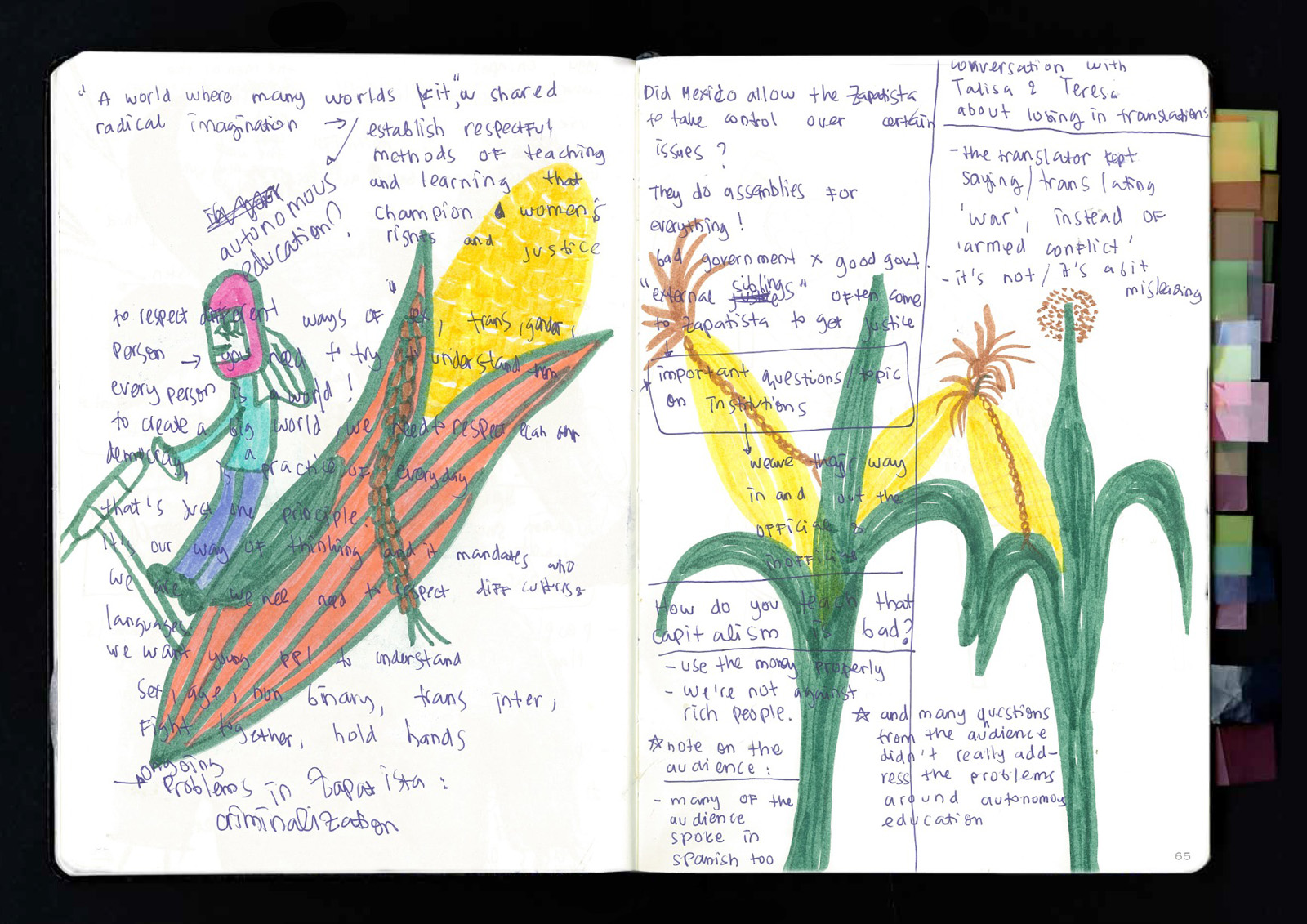

I hung onto my notes and drawings tightly. I turned their stories into my own glossary of keywords. I turned them into spoken words, poetry, and narrow passageways that allowed me to absorb the gist of the conversation. I wanted to catch all the important words and keep them carefully in my notebook. I did not want to lose them. How could I make sense of the relation between drawing in a notebook, the Zapatistas’ act of telling their stories, and listening to their stories? How can the entanglement between these processes be explained as a productive tool leading to transformation process? Something transformative does not need to be a big thing. In my case, it is an understanding that resulted from a simple activity: the magic of listening while drawing.

The request not to take photographs in order to respect the Zapastistas’ identities is a gesture that needs to be guarded and protected, and to me is associated with their face coverings. Together this could suggest a lack of transparency, though as Édouard Glissant argues in the Poetics of Relation (1997): the oppressed have the “rights to opacity,” and should be allowed to exist in ways they want to establish their existence. Wearing masks can make everyone appear equal, which in the collective struggle could mean concerns that are shared. The documentary People Without Faces (2016), a title I find problematic, links wearing masks to the demand to be listened to by the authorities. Within the Javanese context, “losing face” is a phrase to refer to a situation where someone is feeling ashamed due to their inglorious acts. In contrast with this, wearing a mask is the Zapatistas’ conscious statement of pride and courage. There was a conversation between the filmmaker and the Zapatistas where one member said: “In order for them to see us, we covered our faces. So that they would call us by names, we gave up our names.If you want to see who’s hidden behind our masks, then take a mirror and look at yourself.” Wearing masks amplifies the demand; they share their stories, and walking slowly like snails, or caracoles, they move forward nonetheless.

Drawing is part of my everyday activity with my family — mainly with my daughter, Cahaya. Drawing together serves as a moment to share observations and build conversations. I asked Cahaya why she likes drawing so much. She said she likes it because drawing is like “opening up a spirit portal,” a use of words that comes from the American animated series, Avatar: The Legend of Korra. I introduced Cahaya to the first in the series — Avatar: The Last Airbender, as I watched it when I was younger. The avatar (Avatar Aang, then Avatar Korra) is tasked with restoring balance between all elements (nature – technology, spirit – non-spirit, human – nonhuman) and bringing peace and justice to the world. A spirit portal emerges from a battle between Korra and Unalaq who wanted to release Vaatu, the spirit of Darkness and Chaos, fused with the Dark Spirit, and take control of the world. This might seem unrelated, but Avatar made me think about drawing differently. I see the conflict between Korra and Unalaq as the struggle against the leader who would do anything to achieve power, even when that brings ecological destruction and injustice. In the aftermath a spirit portal emerges that provides the opportunity for the human to visit the spirit world, and vice versa. Previously in the series, the human and spirit world had been separated for a long time resulting in chaos and a sense of imbalance. As the avatar, Korra has the power to close the portal and retain her authority to enter the spirit world. Instead, she decides to keep it open, leading to a new age where human and nonhuman learn to live together in peace. Like the spirit portal that opens up new possibilities for realigning with the spirit world, drawing opens up different ways of seeing, inhabiting spaces, and doing communication. Drawing helps me to hear better.

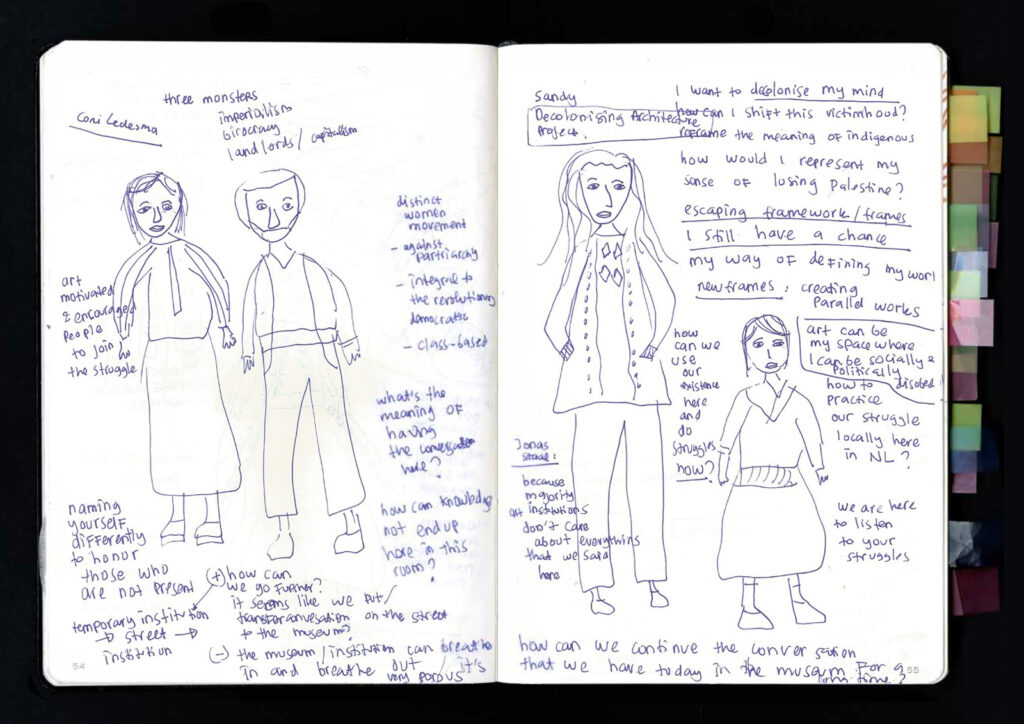

So it goes. I drew everything that is in front of me. The scene of the meeting — the speakers, the two corns painting (Corn Series, Iliada Charalambous, 2021), some female members of the Zapatistas who sat quietly and made embroideries. I drew the table with food for Zapatistas and participants at Moira. I saw the new mural that was made by a Zapatista member with a corn-shaped propeller and two people on it. At home, Cahaya and I made a different version in our notebooks. In Cahaya’s version, the corn propeller has a girl roller-skating across it. principles of “leading by obeying” and thought of the corrupt government in my home country.

I heard the stories about the ancestors’ struggle, the needs for organizing and liberating the people, autonomous municipality, clandestine healthcare, governing ourselves while passing down the spirit of the struggles of the repressed communities, doing all of this while developing autonomous initiatives to survive every day. Storytelling is embodied autonomy. I listened to these stories that could go on forever, while thinking along with the struggles within them.

Then, these pages emerged. Seven principles of Zapatista autonomous governance:

1. Serve and don’t self-serve

2. Represent and don’t supplant

3. Construct and don’t destroy

4. Propose and don’t impose

5. Convince and don’t conquer

6. Go below and not above

7. “Govern by obeying [Mandar obedeciendo],” cited in Margaret Cerullo, “From Below and To the Left: Zapatista Autonomy and Resistance without End,” University of Massachusetts Amherst, 18 September 2017; umass.edu/resistancestudies/sites/default/files/margaret_cerullo-_zapatista_talk_sept_2017.pdf.

AUTHOR

Nuraini Juliastuti

YEAR

2022

PUBLISHER

K. Verlag

Van Abbemuseum

KEYWORDS

Zapatista

Drawing

Listening

RELATED WEB

K.Verlag Publishing Berlin

1 — I attended Zapatista meetings in 2021 at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven and Auto Centrale Utrecht (ACU), a political cultural center and squatting movement in Utrecht with a library, vegan cafe, film house, and performance space. The diverse landscapes align with the heterogeneous networks that facilitate Zapatista delegations in the Netherlands, or the “Journey for Life”—the name of their journey. The delegation’s activities are managed by Gira Zapatista va a Holanda, and meetings individually organized, each with their own focus and together engendering listening practices that invite occasions to make drawings. The meeting on 21 October 2021 organized by Iliada Charalambous, Sophie Mak-Schram, and Denisse Vega de Santiago saw the delegation meet with the Kurdish Women’s Movement in the Van Abbemuseum’s installation of the Museum as Parliament, a project by Democratic Federation of North-Syria and Studio Jonas Staal; see jonasstaal.nl/projects /museum-as-parliament. The following day, a conversation about autonomous education took place at ACU, co-hosted by myself and Teresa Borano (Fossil Free Culture and Disobedient Art School), before which I met the delegation at Stichting Moira through my friend Ying Que; as lead-up, Moira organized a city tour on radical history during which I encountered The Other Stories: The Tales of Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos zine, a copy of which Julian Togar Abraham at the Amsterdam Assembly had given me two weeks earlier. Togar himself was given the zine by his colleague, Daniel Aguilar Ruvalcaba, who told me that Diana Cantarey had translated the stories, designed, and made the zine. On 3 November, I attended a meeting at Dokzaal arts community and kitchen in Amsterdam titled “The Rebellious Zapatista Voice” and met my friends from the IMAGINART (Imagining Institutions Otherwise: Art, Politics and State Transformation) research group — Carine Zaayman, Aria Spinelli, and Yazan Khalili.

2 — Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 7.