This essay is about Indonesian migrant workers, their writing, and the possibility to consider that as their own archives. Writing is a tool for archiving, and writing enables the migrant workers to document their own lives. The narratives of the migrant workers do not always make it into the narratives of the archival systems of the state. In contrast, the migrant workers’ writing emerged as their own archives. Writing can also be used as a mechanism to endure the unjust working and living conditions. Migrant workers are the active ingredients of the archives: being a migrant worker is an embodied experience, which remains an important source for writing stories. In the case of migrant workers, writing means to establish an alternative system of recording and archiving. I argue that the migrant workers’ written texts are a performance of self-care and a form of embodied archiving.

This essay is about Indonesian migrant workers, their writing, and the possibility to consider the texts they produce as migrant workers’ archives. The idea of developing a relation between migrant workers’ literature and its position as archives is shaped by my involvement in the “Afterwork Reading Club”, a project run by Kunci Study Forum and Collective in 2015 and 2016, which focused on reading and writing together with migrant workers. Kunci is a Yogyakartabased research collective, which focuses on creative experimentation and speculative inquiry, combining theory and practice, which I co-founded in 1999.1 The Afterwork Reading Club was organised during Kunci’s participation in Para Site’s International Art Residency in Hong Kong. It was initiated as part of Para Site’s Hong Kong’s Migrant Domestic Workers Project. Afterwork Reading Club culminated in the publication of Afterwork Readings—an anthology of short stories and poems dealing with various workers’ issues. 2

My involvement in Afterwork led to other projects related to migrant workers in different social contexts. I was one of the selection team members for the Taiwan Literary Award for Migrants (TLAM) in 2017, and I had the opportunity to take part as a mentor in the “Doing Visual Politics” workshop in Kathmandu in 2018.3 During the workshop, I developed a class on the topic of “Different shapes of archives: Nepali migrant workers and their families”. In 2019, I took part in a residency organised by No Man’s Land Residency: Nusantara Archives project in Taipei. During my Taipei residency, I developed a project called “Archives as Migrants”.4 In this essay, I use my personal experience and knowledge of migrants workers’ reading materials and migrant workers’ writing as points of reference.

Indonesia has been regarded as one of the main sources from which the figures of the workers‘ outflow to various other countries is high.5 The rise of the number of Indonesian migrant workers reflects the intensified mobilisation motivated by necessity as breadwinners, to support the family, and the global mood of precariousness that cannot be defeated by staying at home. The economic contribution of migrant workers is huge: Indonesian migrants managed to send US$ 8.8 billion to Indonesia in remittances in 2018.6 Within the Indonesian context, migrant workers are called pahlawan devisa, which literally means the “heroes of the foreign currency”. Such a label denotes their important status. At once ironic due to the fact that migrant workers are prone to various forms of abuse—by their employers and in the form of blackmailing to smooth over administration difficulties by those working along the chain of the labour dispatch agents.7

What also shapes the topic of this essay is my PhD dissertation, in which I articulate the development of community-based resources through reimagining politics of access, sharing and distribution, economies of performance, conditions of archives and ways of archiving. The involvement in Kunci’s Afterwork has shaped my knowledge about migrant workers and their capacities as writers and knowledge producers. My own PhD research shows various archiving and documentation practices as strategic and creative ways for dealing with problems around access, embedded in the growing appreciation of historical values and thinking about the future. In thinking about the writing by migrants as a form of archiving, I propose to see the voices of migrants as important voices for the future.

To categorise certain materials as archives emphasises their historical meaning. Some materials are significant because they are scattered and therefore need to be collected, otherwise they will be gone and their archival importance lost. An archive, or a collection of materials is often referred to in Indonesian as dokumen, or document. In everyday conversation in Indonesia, the word “archive” and “document” are largely used interchangeably. There are anxieties about “the lack of culture of documentation” in relation to visual and photographic material in Java as observed by Karen Strassler.8 The reason why I bring up the relationship between archives and the documents is not just to show that they exist in different forms, but to underline that the life of migrant workers, intertwined with their engagement in archives themselves, are often caught up in the reality of the complexity of state-made documents. While documents reflect the operationalisation of different authorities to exercise their power to regulate the relational position between the state and individuals, the migrant workers’ possession of certain documents defines their social and political status. Based on the documents in possession, they are categorised as “documented” or “undocumented”, where the latter category defines them as illegals and therefore prone to be subjected to unjust laws.

My conceptualisation of migrant workers’ literature as migrant workers’ archives is based on their position as writers and how their writings are positioned as archives. The migrant workers’ writing narrates the stories of these workers’ lives. In the context of the migrant workers’ writing practices, writing demonstrates an attempt to document their own lives. The migrant workers’ collections of writing are archives, because they record the life of the migrants themselves. Writing for migrants is an act to reclaim a sense of authority towards their own time and to reimagine the future. This leads to another set of issues related to why migrant workers write: it includes discussion about various factors that support a conducive writing environment. Here I want to assert a view that writing performs an act of self-care.

Archives as well as archiving processes are contested sites. Even on a small scale, the basis for deciding whether a certain set of materials is valuable for archiving practices is dependent on negotiation processes.9 The general anxiety about the lack of culture of documentation, as observed by Strassler, is accompanied by another kind of anxiety related to the availability of archive-based institutions, where the stories of migrant workers may not be categorised as archives at all. Writing emerged as a practice with the potential to convey important messages and to govern the politics of archiving. How can the writing process, coupled with developing archives be defined? How can this be portrayed as a performance of self-care? These are the questions that I use to guide this essay.

I intend to create a connection between writing and archiving, and at the same time I want to emphasise that writing is a laborious task. This is a particular concern for migrants who write, since migrant workers do not have much free time. Indonesian migrant workers have been studied intensely and dissected from many angles by various scholars, however, a raw and realistic picture of how migrant workers, or workers in general, have to endure their everyday hardship is often only found in the writings produced by the migrant workers themselves. This was what made Kunci turn to the migrant workers’ writing in the first place. During the New Order era in Indonesia, the struggle by labourers over basic rights was regarded as part of the people’s movement against the state. The murder of the labour activist Marsinah in Surabaya (East Java Province) in 1994 is a case in point, where the labour mobilisation to fight for better wages was dealt with by heavy-handed military policing.10

Wiji Thukul, a labourer, poet, and political activist before he was made to disappear by the Indonesian military, produced many poems that narrate the life of labourers under the New Order regime. Wiji Thukul’s poems shed light on the direct relation between the labour movement and activism against the New Order. His work was circulated widely, used and appropriated for many rallies leading up to the Reformation period in 1998. I quote here an excerpt from Wiki Thukul’s work titled Satu mimpi satu barisan (One dream one line):

there is my friend Sofyan in Lembang

today he is selling meatballs, after he got fired from the factory

he undertook a strike because he wanted an improvement

all of this is because of his wage, yes, his wage

there is a friend called Sodiyah in Ciroyom

her husband is now lying sick in a bed in their rented house

he is working in a tea factory

he looks so pale, down with typhus

yes, he is down with typhus

there is also Neni

and my friend Bariah

she is a former worker in a sock factory

now she is a worker in another factory

she is fired, yes she is fired

her error: refusing to be treated unjustly.11

This rest of the essay is divided in several parts. In each part I attempt to illuminate key points to discuss writing as an intellectual product and an archiving practice. In the first part, through an explanation of the Afterwork Reading project, I introduce the intellectual position of the migrant workers. In the second part, I problematise the meaning of the archives as a collection of material that carries historical meaning and the official meaning attached to a document, a piece of paper that is often used to prove the identity of a person. I explore the layered dimensions of archives by discussing the documented and undocumented migrant workers. In the third part, I discuss the definition of sastra buruh migran, or migrant workers’ literature, the infrastructure to sustain it, and how the works produced are valued in a wider Indonesian literary landscape. In the last part, I go back to the narratives of the migrant workers’ writing to discuss what the act of writing means to them. I reflect on writing and other tools of archiving in the everyday to speculate on what would happen if migrant workers were stripped off everything that makes it possible to write or record something.

Afterwork Reading Club: Woman Migrant Workers, Stealing the Time, Reading

A certain sense of minor anxiety was felt at Kunci when we were approached by Para Site to work with Indonesian migrant workers in Hong Kong. While migrant worker-related issues have been under scrutiny from scholars, non-governmental organisations, labour activists and mass media, we wanted to take a different route. When we envisaged how we would undertake the project, we paid attention to the novels or short stories written by Indonesian migrant workers. The book Empat Musim Bauhinia Ungu (Four Seasons of the Purple Bauhinia), a novel written by Arista Devi, the pen name of Yuli Riswati, a migrant worker who lived and worked in Hong Kong, was one of the main references that we used to conceptualise Afterwork.12 We observed that the main narrative revolved around migrant workers’ hardship and suffering. One of the main points that we made after conducting preliminary research was that “In these works we meet different characters falling in love, a traveller getting lost, a prolific writer, a woman in search for an identity, or a mother taken over by deep longing. In short, the spectrum of subjectivity in the realm of fiction is not bound to, nor it can be ‘domesticated’ by the stereotypical category of migrant workers.”[13] We considered Jacques Rancière’s The Night of Labour (1998), in which he argues that the workers’ writing performed an important political action that disrupts the established division of labour.[14] We perceived this as a productive intellectual stance that allowed us to move away from associating workers with just menial labour. In the project description, we wrote that “by featuring and endorsing the creation of narratives by migrant workers that revolve around their refusal to be domesticated by an identitarian label, we can tease out the different ways they exercise their rights to think critically.”15

At the same time, I was thinking about Kamala Visweswaran and her book Fiction of Feminist Ethnography (1994) in an attempt to understand the meaning of ruins, or something that is half abandoned, as a key point to define what is important and less important in examining various archiving projects in my own research.16 Fiction, as stated in our introductory text for the Afterwork Readings, should not be seen as a mere literary form, but rather, “as a narrative strategy, which can represent the subtle moments of contestation within the process of subjectivity construction.”17 In taking the migrant workers’ literary works as a site for exploration, we moved away from the dominant reading of migrant workers and public advocacy attempts, which focused on basic labour rights, systematic abuse, and vulnerability.18 Throughout the organisation of Afterwork we relied on the participation of the migrant workers-cum-writers. At the same time, our project gave rise to the development of new writing by migrant workers.

In the organisation of Afterwork, we focused on Indonesian women migrant workers in Hong Kong. Such a focus was informed by our observation that the writings with migrant workers‘ themes were mainly written by women migrant workers. The archives discussed here are not only about migrant workers, but they are the stories of women. For all, the lack of time is an important element that regulates the relation between migrant workers and their employers in everyday life. Time is always precious. Reports state that the majority of domestic helpers in Hong Kong work excessively long hours—11 to 16 hours a day, over 70 hours per week.19 Among the migrant workers community in Hong Kong, Sunday therefore is a sacred day, as it is the only day when they can relax and don’t need to think about work. Victoria Park is the hotspot for Indonesian migrant workers to enjoy their free time. The activities of the workers in the park have been the source of news for various journalists and inspiration for writers and film-makers. For example, Lola Amaria, the Indonesian director, produced a film called Sunday in Victoria Park (Minggu di Victoria Park) in 2010.20

After work hours should not be taken for granted. In many cases, one has to fight for them. This laid the groundwork for us to organise a series of reading groups with Indonesian women migrant workers, which later was referred to as the “Afterwork Reading Club”. The word “Afterwork” in Kunci’s project refers to the “after working hours” situation, a period of free time, a special time, allocated for the workers to rest. In our project, we complicated the existence of after work hours and how the workers manage that time with the organisation of reading activities. Afterwork Reading Club served as a platform where migrant workers engaged in reading. Reading is regarded as an activity that requires time. On the one hand, reading is part of the working method of some professions, on the other hand, reading is at times only possible when there is free time. Through the organisation of Afterwork Reading Club, we encouraged reading as an activity to acknowledge the preciousness of free time and the luxury of reading at once (Figure 1). This also was another reason why we chose fiction as a reading material during the reading group sessions.

Figure 1: Afterwork Reading Club session in Hong Kong,

which took place in artist Jessica Fernando’s flat in Tai Wai; photograph courtesy Para Site

In order to capture how migrant workers deal with time, while reflecting on the intellectual production in their writing, we titled the result of preliminary research in Hong Kong “A Room of Their Own.” The title was inspired by Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own (1929).21 We considered Woolf’s argument that the struggle for intellectual freedom for women is always intertwined with economic autonomy and the possession of an independent space. We selected various texts, ranging from existing short stories written by migrant workers to stories written by other Indonesian writers. In selecting the texts, we were thinking about the architecture of the domestic spaces inhabited by migrant workers—living rooms, kitchens, dining tables, bedrooms—and the park. The reading materials for the reading group sessions included texts such as “I have to go home this Lebaran” (Umar Kayam), “Kitchen Curse” (Eka Kurniawan), “Layout” (Sapardi Djoko Damono), “Instincts that Give Foundation for Creations” (NH Dini), “A Dog Died in Bala Mughrab (Linda Christanty) and “Sleeping Partner” (Hanna Fransisca).22 In their own ways, these texts narrate various dimensions familiar to migrant workers—a sense of longing, home, the drive to create, and the obligation to be stuck in different homes doing chores for other families.

The project culminated in the development of an anthology of short stories and poems by migrant workers titled Afterwork Readings (Figure 2). Some stories from the anthology still stick in my mind. These stories recount the amount of distress that migrant workers have to endure on a daily basis. Enjoying free time, secretly doing something enjoyable, or organising small, accidental acts of revenge emerged as liberating acts. Indira Margareta’s work “Light for my pen” is one of them.23 She writes:

It wasn’t any wonder I found myself typing in the dark. I had to force my eyes to find the letters on the keyboard, so arranging a sentence was a long and painful process. I also had to type lying down on my bed, since if the grandma knew I was still awake in the middle of the night she would throw a tantrum and tell my male employer. Therefore, I put my laptop on my belly, pressing my fingers on the keyboard slowly and with difficulty. My cruel grandma always found a way to pick at my mistakes and tell them to the male employer. She must have thought that finding my mistakes would make her a heroine. Usually, after dinner time, she would proudly recite my mistakes one by one in front of my employers. He was rarely at home, so he entrusted me to his mother. And she was a vile slanderer.24

Figure 2: Afterwork Readings book; photograph Nuraini Juliastuti

Another story from the book that I like is “The tragedy of the soy sauce finger” by Epha Thea.25

The woman peeked out from behind the kitchen door. She whimpered in pain, holding her stomach, feeling nauseous and hungry. Hungry not because there was no food, but because she had lost her appetite. Her employer’s family and their five guests were sitting at the dining table and enjoying the meal that she had served of chicken seasoned with soy sauce. Between the sounds of the chopsticks against the bowls, she heard a comment from one of the guests, “I think this is the most delicious soy sauce chicken I have ever tasted.” The woman behind the door could not endure it any longer; she went to the bathroom again. For the umpteenth time, she threw up all of the contents of her stomach. Then she sat down limply behind the bathroom door; her tears flowed slowly. She was heartsick as she wept over her index finger, of which several millimetres had been sliced off, and, along with her blood, had become part of the dish she had served for her employer’s dinner.26

Politics of Archives: On Collecting and Writing as Archiving

The condition in which things are scattered or perceived to be scattered may motivate a collector: dispersal is something to be resolved through an act of compiling, in order to make them a coherent whole. Many collectors have tried to describe their practices as developing or building a collection. To collect is to erect a building constructed from previously scattered material. It seems apt to consider Rudolf Mrazek’s concept of the “engineer” in seeing the works of the collectors.27 Like engineers, who work to realise their plans in conceptually designed buildings or infrastructure, collectors also try to perform their vision in their collections. The main task of engineering work in collecting is concerned with how things are ordered and reordered. According to Susan Stewart, time in a collection is “not something to be restored to an origin; rather, all time is made simultaneous or synchronous within the collection’s world”.28 The process of ordering and re-ordering changes the linear logic of time, and as a result history is replaced with classification.29 A collection is at once a historical project, albeit as Stewart reminds, a “self-enclosed” one. A collector thus is an engineer who orders and re-orders time.

Collecting is a way of practising an independent historical project. It leads to a further dimension about the authorisation process by official institutions. Collecting enables a collector to take the role of the authorities by authorising the existence of a certain archive. Jacques Derrida argues that “the technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content, even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future.”30 Derrida’s statement indicates that there is limited freedom in conceptualising the future. Furthermore, Derrida asserts that an archive is like a “pledge”, which functions “like every pledge [gage], a token of the future.”31 Following Derrida, I go back to the notion of fiction as a narrative strategy and part of the subjectivity construction, which Kunci used when we conducted Afterwork project in Hong Kong. I use this to develop a connection between collecting and writing. I consider Derrida’s argument about the function of the archive as a token of the future to think about the meaning of fiction in migrant workers’ writing practices. Migrant workers write fiction as a strategy for endurance and taking back time. A document, or dokumen, provides an official status. It is a state-issued paper. A document serves as the official record of something, or someone. Such official dimension enables a certain document to act as the representative of the authorities. On an everyday level, it serves as the mechanism through which an individual is identified, recognised and labelled. This kind of document is referred to as bukti identitas, proof of identity. An identity card and the bureaucratic, and sometimes corrupt, machine to produce it, defines the politics of access to various forms of basic necessities.

In the Indonesian context, owning a KTP (Kartu Tanda Penduduk), or a resident card, forms the formal requirements to be considered for various forms of access, positions, and job opportunities. As part of ‘disciplining Tionghoa’,32 for example, the KTPs of the Chinese Indonesian were marked with the special code to indicate their ethnic identity. In the earlier phase of the New Order regime, President Soeharto issued a presidential decree Keputusan Presiden Nomor 240 Tahun 1967 regarding the Indonesian citizens by naturalisation. The decree stated that the naturalised citizens were advised to change their names according to the Indonesian naming system. The issuance of this policy, combined with the diplomatic crisis between Indonesia and China following the 1965 event, forced assimilation attitude and the escalation of latent racism tendencies towards the Chinese Indonesian, which resulted in the Chinese Indonesian decisions to discard their Chinese names in favour of Indonesian sounding names in their KTP.33

A state-made document has the power of othering. Based on the correct document possession, a migrant worker is referred to as “documented” or “undocumented”. Such a status creates the boundaries from which a migrant worker navigates their relational position with state authorities. A wrong move may result in the confiscation of a document. In the case of migrant workers, the dispossession of the documents has the potential to not only make them the other in society, but also being treated unjustly. There are also cases where state agencies do not only overcharge migrant workers, but also keep their passports until the workers are able to pay the entire amount of the fee.34 The authoritative value of the documents proceed from the authorities who produced them.

The official nature of a document and the documented and undocumented status of a migrant worker provides an avenue to reflect on other dimensions to form an archive. The making of an archive does not only inform what things to include or exclude, or what aspects to remember and to forget. Rather it often builds on the consciousness that the possibilities of being apprehended and deported are inevitable. Here I want to make a point about the possibility of being apprehended and deported as important aspects of remembering and forgetting. There is a physical dimension attached to them, which transforms into a sense of alertness and fear and makes writing an embodied activity. To be able to write, but more importantly, to be able to work and live well, is to struggle for both a physical and intellectual existence. It is therefore an act that is equal to erecting a building of archives.

To refer to writing as building an archive takes us back to Walter Benjamin.35 Benjamin describes the work of a book collector as the development of a dwelling. A book collection in Benjamin’s sense, represents the history of acquisition, but also provides the chance to encounter and find significant matter. The collecting project discussed in Benjamin’s writing focuses on books that have become classics: they are written by the greats of art and literature. Migrant workers develop their own building, which may not be grand, but that is constructed from the stories of their lives.

Writing is a practice that supplies the migrant worker with the energy and power to document their own lives. It serves as an activity that can be mobilised to endure unjust working and living condition. In the case of migrant workers, writing provides the power to document their lives from a personal perspective. The stories of migrant workers often do not make it into the archiving systems of the state. To be able to write is therefore to perform an act of self-care.

Writing enables the migrant worker to take back the power to reclaim a fraction of safe space. The migrant workers-writers transform their physical experience of being a migrant worker into an intellectual product. To go back to the notion of collecting as erecting a building, the migrant workers emerged as both migrants and intellectual bodies. Writing is part of their embodied activities.

Sastra buruh migran: Definition, Infrastructure, Valuation

The literary works of the migrant workers is known as sastra buruh migran, or migrant workers’ literature. Sastra buruh migran is establishing itself as a recognised genre in the local literary landscape. The works of the migrant workers can easily be found in bookshops. Along with the establishment of migrant workers as a subject of study, the interest in their own writings is now also growing.36 The migrant workers-writers may refer to their writing practices as a useful activity. However, they remain relatively obscure. They are not usually considered as part of the Indonesian literary canon.

During the organisation of Kunci’s Afterwork Reading Group, the circulation of the migrant workers’ writing happened through local newspapers where they worked, personal blogs, and social media platforms. In other cases, their writing was published through self-publishing services. The possibility to advance the writing skills of the migrant workers is facilitated by the cosmopolitan dimension of this learning environment. Many migrant workers participated in online writing courses facilitated by writers’ forums. For example, a branch of the Jakarta-based Forum Lingkar Pena (FLP, The Circle of Pen Forum) in Taipei functioned as one of the places where migrant workers learned to improve their writing skills. FLP is considered the biggest writers’ community in Indonesia.37 During Kunci’s research in Hong Kong, my Kunci colleague Brigitta Isabella found that the FLP also organised mobile libraries in Victoria Park and contributed to the dynamics of the Sunday activity of the migrant workers.38

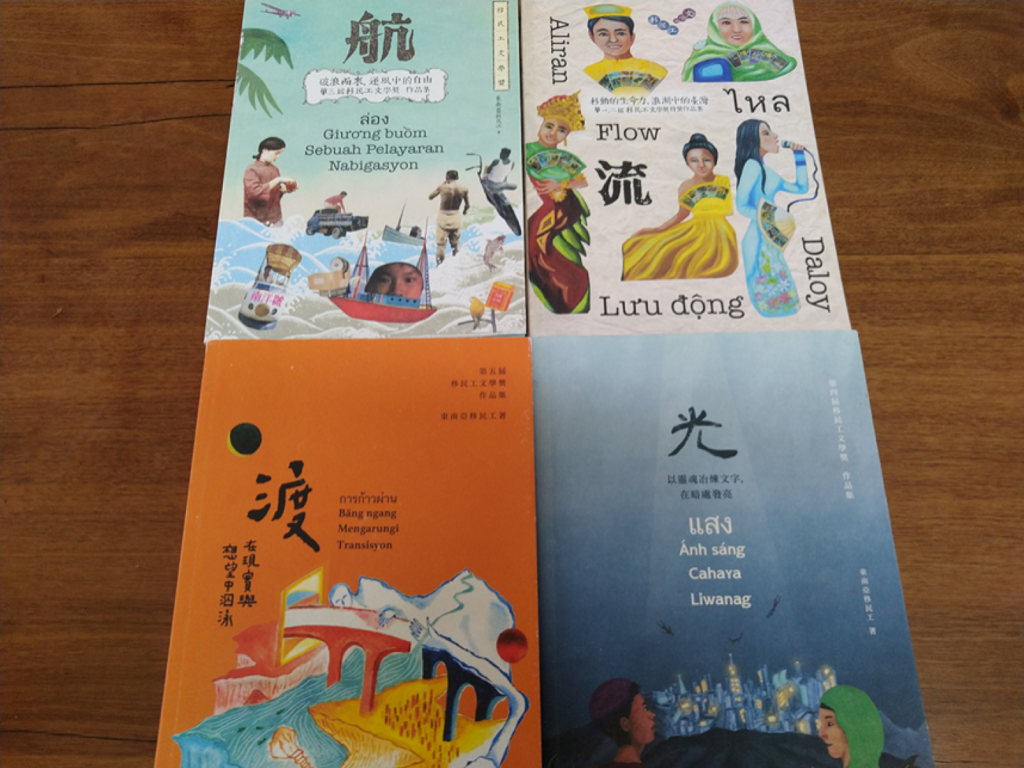

Other migrant workers were active participants of various writing competitions organised by the overseas branches of Indonesian mass media. It suggests that writing competitions are part of the wider cultural-based competition a la Indonesia, which has helped nurturing the rise of new writers. At the time of writing this essay, Taiwan Literary Award for Migrants (TLAM) serves as the most active literary festival for migrant workers’ writers. TLAM started in 2014, and was initiated by the journalists Chang Cheng and Yun-Chan Liao. They also set up a bookshop called Brilliant Time. The bookshop provides a space where people can read various works in the languages spoken by migrant workers’ communities in Taiwan, such as Indonesian, Thai, Filipino, Cambodian, and Vietnamese. It also serves as the space to organise workshops and discussions which focused on migrant workers (Fig. 3). TLAM and the bookshop are designed to be a useful platform to support migrant workers in Taiwan. More than just a writing competition, TLAM recognises the urgency to appreciate the migrant workers’ writings.11

Figure 3: A scene from Brilliant Time Bookstore’s book club activity in Taipei Main Station; the photo was shared by Wu Ting Kuan, a former programme coordinator of the Taiwan Literature Award for Migrants through Facebook Messenger; photograph courtesy of Wu Ting Kuan

During my residency period in Taipei in April 2019, I had a conversation with a Taipei-based cultural activist in which he told me how a famous Indonesian poet once told him that he would never consider writing by migrant workers as part of proper literature.[39] According to the poet, their works would be best described as mere “porn” instead. As I hope to investigate the appreciation of the literary figure further, my essay provides a little room to consider this further. I want to move beyond what is good and bad, which is often referred to derogatively, labelled as “porn”. At the same time, I want to dwell on the meaning of “porn”, and emphasise its stimulating capacity, to make a connection between writing and a certain sensibility. This means to regard writing as a task that is situated in between myriads of practicalities and functions in everyday life.

I will explore this through my experience as one of the selection team members for Taiwan Literary Award for Migrants in 2017. Reading all the workers’ submissions made me think of them as a compilation of dreams, visions, hopes, and plans to achieve it. How could I evaluate texts that also capture dreams and hopes? These are hopes and dreams of a mother who decided to work as a carer far from her family and everyone she loved, of a father who decided to leave the family and worked as a ship’s crew member, of a young woman who saved to continue education overseas. In every evaluation process a particular work will be valued higher than others; there tends to be one work that is regarded to be more original, innovative, coherent, complex, mature and have depth. At the same time, I believe that every dream is valuable. Each dream is original, coherent, complex, mature and has depth, which should not be assessed through a set of limiting indicators.

During the selection process, I read 131 texts, from which I selected 27. At the end of the selection process, only ten made the final cut. I imagine that every text I read had gone through a long process, including time limitations, not having sufficient production tools, and the persistence of wanting to write. Some were typed neatly on a computer or mobile phone, others were handwritten on paper. The varied shapes of the writing indicated the complexity of the writing process and the operationalisation of cultural production in the intellectual ecosystem of migrant workers. These aspects need to be considered in valuing the migrant workers’ writings.

They are the products of stealing time, but most importantly, to follow Rancière, they perform as an intellectual work of labour.40 Time stolen from working hour, again to follow Rancière, and allocated time to write must be understood as the context that provides insights into the emergence of knowledge production outside the mainstream. I thought about the sastra buruh migran label when reading the texts during the assessment process. Rather than fitting them into the strict categorisation of literature, I decided to look closely at the sentences written in a short story or poem that I read. I reflected on the production environment that surrounded it and thought about what was bubbling beneath it. This is how the standardised categorisation of evaluating what is “good literature” can be disrupted. The lines showed resilience, reimagined fragility, strength, a struggle for love amidst hard work and little money. I used five aspects to value the works in the competition: rhetoric, writing skills, originality, aesthetic coherence, and resonance. They might sound like standardised indicators, but I perceived this as my invented mechanism to appreciate the migrant workers’ aspirations to develop their writing capacities. These indicators were my tools in assessing how writing might project a bigger agenda.

Themes such as rough employers, or caring and loving employers, violent working environments, longing for the family at home, cultural shock, love affairs and living in jail emerged as common threads throughout the writing that I read for the selection. They are often regarded as the typical issues migrant workers have to deal with, but seeing the representation of migrants’ narratives in the mass media seems to simplify a lot of things. A chronological way of telling the story, or framing a story in the form of a letter, for example, came up as repeated tropes in the works read. Rather than seeing this as predictable narrative forms, it made me rethink the value of writing names in a straightforward manner. Writing down a certain name is an important way to think, it is part of the workers’ attempt to establish their personal identities. In everyday life, they are often almost nameless, only regarded in terms of their physical power. Of the ten texts that I selected, some of them reflected a certain kind of anger. It is the same kind of anger that I felt when reading “Light for my pen”41 or “The tragedy of soy sauce finger”42 referenced at the beginning of this essay. But I would rather not see them as the expression of anger: perhaps it is more appropriate to see them as the representation of thoughts and feelings in dealing with the complexity of life in Taiwan. I see these writings as a way of making peace, crossing the wide spectrum of life, ranging from economic difficulties to acts of violence, of love entangled with wounds from the past as the victim of sexual violence, to finding a mechanism to survive from the male employer predator. In their own way, these writings emerged as a mechanism through which the agency of a migrant worker is leveraged.

Some of the works that I selected for TLAM were published in an anthology titled Cahaya (Ray of Light, see Fig. 4).43 Each short story in the book is accompanied by a separate text from the authors stating the reason or aspects that made them write. Aiyu Nara, for instance, states that writing is a medium, a tool for conveying messages to a wider audience.44 Another writer, Rahayu Wulansari, contends that writing is a form of therapy, a vessel through which anxieties and feeling stressed can be expressed.45 Along similar lines, Safitrie Sadik states that writing is a form of expression.46 Working conditions are often characterised by boredom, while imagination comes unexpectedly.47 In a more reflexive tone, writing is perceived as a reminder.48 Etty Diallova, the winner of the TLAM competition in 2017, reminds us that the stories migrant workers-writers tell are often about women, and mothers, who are willing to sacrifice their own happiness for the happiness of other family members they love. Her short story, “Red”, is about a woman who has fallen pregnant from her male employer, and decides to abort the pregnancy.49 The last paragraph of the story reads:

For money, for life, I have committed this sin. People only knew that being a migrant worker brings a lot of money. We can build a house in our kampong and earn a monthly salary that is potentially bigger than that of the office worker in Indonesia. People might see our beautiful and happy smile, especially from our social media accounts. But no one knew that there are many dark gloomy sides that we experienced here, in the adventure that we chose. No one knew our broken hearted tiredness, and never ending pressure. Just like my red.50

Figure 4: Selected essays of the Taiwan Literary Award for Migrant s (TLAM) have been turned into a series of publications, including Cahaya (bottom right), among other books; photograph Nuraini Juliastuti

Arista Devi, aka Yuli Riswati, state clearly that writing is an act of testifying.51 To write is to tell people about salient matters that they know very well, and as they describe in one of their short stories, these might be the matters that only they, or other women migrant workers, know about. Below is an excerpt from Devi’s short story, “Violet Testimony”:

Arggh! I want to scream. The news article is wrong! Why don’t they write that the reason for the accident is because the woman was lost and senseless, because her spirit had been sliced to shreds? The lady boss had tortured her and the man boss had raped her. And the woman only had me, just me. They should have asked me for my testimony because I know everything. She always complained about all of the horrendous treatment that she had to endure. I am willing to testify! I want those evil employers to be tried and sentenced because they caused the death of an innocent person! It’s scorching hot. I suddenly feel hot, as if I am engulfed in the flames of my own anger. I can feel each part of me, one by one, gradually turning to ash. I’m trying to resist. It turns out that the flaming fire in the trash-burning container will soon devour me completely. I cannot expire before I give my testimony! Yes, God, help me! In these last moments, why is it only now that I have remembered who I really am? I am only a book, a diary with a cover of violet.52

Yuli Riswati is a migrant worker who has also been practising citizen journalism for a long time. Perhaps this can be expected, and a consequence of Yuli’s decision to write and to serve as a witness. In December 2019, Yuli was deported by the Immigration authority of Hong Kong. The main reason was because she wrote reports on Hong Kong protests in Migran Pos, a newsletter for the migrant workers’ community in Hong Kong. Yuli wrote about the Hong Kong protests in Indonesian. Prior to the deportation, she had been in detention on the grounds that she did not have a place to stay, despite her employer objecting against the police detention and writing numerous letters to state that they had extended her work contract until 2021 and guaranteed her a place to live.

Tools of Archiving

In his musings on drawing on fieldwork notebooks, Michael Taussig reflects on the mythical position and almost fetishisation of notebooks by anthropologists.53 Indeed, as Taussig observes, an anthropologist is not the only one who has a notebook, or works with a notebook or a diary. At many stages of their work, any type of intellectual will find a notebook a faithful companion.54 I imagine that a migrant worker who is also a writer must have a notebook, or other tools to write with, but this is not always the case. Not every migrant worker has a notebook, but they usually have a mobile phone.

During my residency period in Taipei, I learned that a mobile phone can be seen as a best friend, a faithful companion similar to Taussig’s description of anthropologists’ relation to their notebooks. I remembered exploring Daan Park, where many Indonesian women migrant workers took their employers’ grandma and grandpa to get some fresh air, or to just enjoy the fresh air and beautiful scenery (Fig. 5). I often saw them making a video call to their families, while attempting to be good carers for the old people. Once I saw a worker who talked with a family member through video call and tried to connect the family and the grandpa in conversation. A Taiwanese friend who also assisted me during the residency said that there would be a new policy in effect soon in Taiwan to regulate video calls among migrant workers. The use of video call during work is considered disturbing. I wonder whether the government would also pay attention to employers who install cameras in their houses to monitor their domestic helpers.

Figure 5: Daan Park in Taipei; photograph Nuraini Juliastuti

Overall, the writing tools that migrant workers use are determined by the conditions that enable them to write. In “Light for my pen”, Indira Margareta tells a story about how she wrote with the help of a torch.55 Some migrant workers have laptops to write on, while others indeed use their mobile phone to type up their stories. But the workers who are living in a prison are not able to use a laptop or mobile phone: they can only write with a piece of paper and pen, and this can only be done with the permission of the prison officer.

I have become friends with some migrant workers in Hong Kong and Taipei. They are all active users of various social media platforms—Facebook and Instagram particularly —and their photos of everyday life activities, which are mostly updated at weekends, run through my newsfeed regularly. But people use mobile phone differently: Yuli uses her mobile phone camera to record events that she would like to share with many people and she usually uploads her writing and recordings on her Facebook account. When she was taken to a detainment centre, Yuli’s mobile phone was also the first thing that was confiscated. What happens when migrant workers lose their writing tools? Suppose there is a time when no mobile phones are allowed during working hours. Can they write from memory? I am going back to Taussig, with his reflection on the notebook, particularly in the case of an anthropologist who lost his, burned in a fire, or left somewhere in the field due to a hasty escape from an army. As it turns out, writing from memory is possible. The anthropologist can write freely like a bird, Taussig states, when writing seems to be freed from the constraints of a notebook.

However magical the position of a notebook is, what is more important, according to Taussig, is the daily habit of writing things down. The writing habit then becomes already embedded, transformed into memory, which can be repurposed by retelling the story, even if nothing seems to be available to use in the beginning. What I am trying to get at here is that a migrant worker can still write, even if they have been stripped of all writing tools. At this point, I remember Yuli and her confiscated mobile phone: in an interview with a journalist after going back to Indonesia, Yuli said that she had “a lot of plans for the future.”56 Some things might appear to wither away, but when writing is worth fighting for we can still expect the existence of the archives of the migrants.

Conclusion

Writing is a tool for archiving. Writing enables migrant workers to document their lives. The narratives of the migrant workers do not always make it into the narratives of the archival system of the state. In the case of migrant workers, writing performs as an act of self-care: it can be used to endure the unjust working and living condition. In this essay, I have elaborated on many examples to show the active participation of the migrant workers to create a conducive environment to write. Various independent writing workshop, mobile libraries, or writing competition provide an alternative infrastructure that supports the process of the migrant workers to become writers. Migrant workers’ writings emerged as their own archives. At the same time, migrant workers are the active ingredients of the archives. Being a migrant worker is an embodied experience: it will remain as an important source for writing stories. In the case of migrant workers, writing means to establish an alternative system of recording and archiving. Writing serves as a tool for inclusion.

AUTHOR

Nuraini Juliastuti

YEAR

2020

PUBLISHER

Parse Journal

KEYWORDS

Migration

RELATED WEB

Parse Journal

1 — Cultural Studies Center. See http://kunci.or.id/ (accessed 2020-04-26).

2 — Afterwork Readings. Yogyakarta: Kunci and Para Site. 2016.

3 — The workshop was initiated by Alan Hill and Kelly Hussey-Smith, RMIT in collaboration with Photo Circle, Kathmandu. The workshop brought together students from various background at RMIT, Swinburne University, Griffith University, and ANU.

4 — In my attempt to conceptualise “migrants as archives”, first, I perceive Taipei as not only the city where the migrants work and live, but also the site of the archives’ production. The transformation of the city into such a site is shaped by how the migrant workers do not only inhabit the city, but also use it as a means to remember, forget and keep on living. Second, I speculate that the archives are a kind of migrant because they fill up the space produced from the opportunities to travel and to work outside of the familiar zones. During my residency, I move in and out the migrant workers’ literary texts, and let these inform how I view Taiwan’s landscapes and learn to master the skills for stretching and loosening time. This essay provides a space to explain this project, but this project, coupled with my previous trip to Kathmandu, serves as the first opportunities in which I explore the relational position between the migrants and the archives.

5 — Riskianingrum, Devi, Sarijati, Upik, Anwar, and Pratiwi, Ratih. The Development of Foreign Workers Policies and Socio-cultural Dynamics of Indonesian migrant workers in South Korea. Jakarta: Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Research Centre for Regional Resources (PSDR, LIPI Press. 2011; Kloppenburg, Sanneke, and Peters, Peter. “Confined Mobilities: Following Indonesian Migrant Workers on Their Way Home.” Tijdschrift poor economische en sociale geografie. Vol. 103. No. 5. December 2012. pp. 530-541; Anwar, Laraswati Ariadne. Stories of Lives and Culture of Indonesian Migrant Workers in Taichung City. PhD Dissertation. National Chung Hsing University. 2013.

6 — Tirtawening. “Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers Lack Protection—How Can Legal Academics Help?”. The Conversation. 26 March 2019. Available at https://theconversation.com/indonesian-migrant-domestic-workers-lack-protection-how-canlegal-academics-help-103785 (accessed 2020-04-30).

7 — Wawa, Jannes Eudes, HCB. Ironi Pahlawan Devisa: Kisah Tenaga Kerja Indonesia dalam Laporan Jurnalistik. Jakarta: Buku Kompas. 2005; Kusumawati, Mustika Prabaningrum. “Ironi Perdagangan Manusia Berkedok Pengiriman ’Pahlawan Devisa Negara””. Jurnal HukumNovelty. Vol 8. No. 2, 2017. pp. 187-200.

8 — Strassler, Karen. Refracted Visions: Popular Photography and National Modernity in Java. Durham,NC, and London: Duke University Press. 2010.

9 — Juliastuti, Nuraini. Commons People: Managing Music and Culture in Contemporary Yogyakarta. PhD Dissertation. Leiden University. 2019. pp.147-181.

10 — Marsinah Fact Finding Team. Laporan Pendahuluan Kasus Pembunuhan Marsinah (The Preliminary Report on Marsinah Murder). Jakarta: Tim Pencari Fakta Pembunuhan Marsinah, Yayasan Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Indonesia. 1994; Supartono, Alex, Thalib, Munir Said. Marsinah: Campur Tangan Militer dan Politik Perburuhan Indonesia (Marsinah: The Interference of Military and the Politics of Labour in Indonesia). Jakarta: Yayasan Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Indonesia. 1999.

11 — Thukul, Wiji. Satu Mimpi Satu Barisan (One Dream, One Line). 11. In Nyanyian Akar Rumput, Kumpulan Lengkap Puisi. 2014. p.99. The translation of the excerpt of Thukul’s poem is mine.

12 — Devi, Arista. Kesaksian Ungu: Empat Musim Bauhinia Ungu (Four Seasons of Purple Bauhinia). Yogyakarta: LeutikaPrio. 2012.

13 — Kunci. “Foreword”. In Afterwork Readings, p. 22.

14 — Rancière, The Night of Labor.

15 — Kunci, “Foreword”, p. 23.

16 — Visweswaran, Kamala. Fiction of Feminist Ethnography. Minneapolis, MN, and London: University of Minnesota Press. 1994.

17 — Kunci, “Foreword”, p. 22.

18 — See Sukamdi, Abdul Haris and Brownlee, Patrick. Labour Migration in Indonesia: Policies and Practice. Yogyakarta: Population Studies Centre, Gadjah Mada University. 2000. Perempuan, Komnas. National Commission on Violence Against Women. Indonesian Migrant Workers: Systematic Abuse at Home and Abroad: Indonesian Country Report to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of Migrant, Kuala Lumpur, 2 June 2002. Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan. 2016; Tan, Win Sherly and Shahrullah, Rina Shahriani. “Human rights protection for Indonesian migrant workers: Challenges for ASEAN”. Mimbar Hukum, Vol. 29. No. 1. 1 February 2017. pp. 123-134; Fatmasiwi, Laras Ningrum. “Public Policy Advocacy Process on the Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers conducted by Institute for Education, Development, Social, Religious, and Cultural Studies (INFEST)”. International Journal of Islamic Studies and Humanities (IJISH). Vol. 2. No. 1. 1 April 2019. pp. 32-49.

19 — Luk-kei, Sum. “More than 70% of foreign domestic helpers in Hong Kong work over 13 hours a day, Chinese University survey shows”. South China Morning Post. 13 February 2019. Available at https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/2185976/more-70- cent-foreign-domestic-helpers-hong-kong-work-over-13 (accessed 2020-05-06); Asia Times Staff. ”HK to review hours limit for domestic workers”. Asia Times. 9 May 2019. Available at https://asiatimes.com/2019/05/hk-to-review-hours-limit-for-domestic-workers/(accessed 2020-05-06).

20 — Amaria, Lola. Minggu Pagi di Victoria Park (Sunday Morning in Victoria Park. A movie). 2010.

21 — Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. London: Hogarth Press. 1929.

22 — Kayam, Umar. “Lebaran ini, saya harus pulang” (I have to go home this lebaran). Kompas. 17 January 1999. Lebaran refers to the celebration to end the holy month of Ramadhan practised by muslim communities in Indonesia. Kurniawan, Eka. “Kutukan dapur” (Kitchen curse). In Cinta tak ada mati: Dan cerita-cerita lainnya. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. 2005. pp.43-51; Damono, Sapardi Djoko. “Tata Ruang” (Layout). In Pengarang telah mati: Segenggam Cerita. Magelang: Indonesia Tera. 2001; Dini, N.H. “Insting yang mendasari penciptaan” (Instincts that give foundation for creation). On Proses Kreatif: Mengapa dan Bagaimana Saya Mengarang. Edited by Pamusuk Eneste. Jakarta: Gramedia. 1983. pp. 110-124; Christanty, Linda. Seekor ending mati di Bala Mughrab (A dog died in Bala Mughrab). Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. 2014; Fransisca, Hanna. Kawan Tidur (Sleeping partner). Jakarta: Komodo Books. 2012.

23 — Margareta, Indira. “Cahaya untuk penaku” (Light for my pen). In 23. Afterwork Readings. pp. 46-51.

24 — Ibid. p.47.

25 — Thea, Epha. “Tragedi Jari Berkecap” (The Tragedy of the Soy Sauce Finger). In Afterwork Readings. p. 125.

26 — Mrazek, Rudolf. Engineers of Happy Land: Technology and Nationalism in a Colony.

27 — Princeton, NJ, and Oxford: Princeton University Press. 2002.

28 — Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham and London: Duke University Press. 2007. p. 151.

29 — Ibid.

30 — Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Translated by Eric Prenowitz.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1995. p. 17.

31 — Ibid, p. 18.

32 — Thaniago, Roy. Disciplining Tionghoa: Critical Discourse Analysis of News Media During Indonesia’s New Order. Master thesis. Lund University. 2017.

33 — Effendi, Wahyu, Prasetyadji, Protus Tanuhandaru. Tionghoa dalam Cengkeraman SBKRI (Tionghoa under SBKRI). Jakarta: Visimedia. 2008, Budi Susanto, S.J. (Ed). Membaca Poskolonialitas (di) Indonesia (Reading postcolonialism in Indonesia). Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. 2008.

34 — Lestari, Eni, Li, Promise. “Fighting for migrant workers in Hong Kong. Eni Lestari interviewed by Promise Li”. Monthly Review. 1 February 2019. Available at https://monthlyreview.org/2019/02/01/fighting-for-migrant-workers-in-hong-kong/. 2019.

35 — Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. New York: Schocken Books. 2007. pp.59-67.

36 — See Indarti, Titik. Representasi Perempuan dalam Sastra Buruh Migran di Hong Kong Asal Indonesia: Laporan Penelitian Studi Kajian Wanita. Surabaya: Fakultas Bahasa dan Seni, Universitas Negeri Surabaya. 2007.

37 — See Arnez, Monika and Nisa, Eva. “Dimensions of morality: the transnational writers’ collective forum Lingkar Pena”. Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia and Oceania. Vol. 172. No. 4. pp. 449-480.

38 — Isabella, Brigitta. “A room of one’s own”. Inside Indonesia. 24 April 2016. Available at https://www.insideindonesia.org/a-room-of-one-s-own (accessed 2020-05-06).

39 — The residency was part of the No Man’s Land Residency: Nusantara Archives project initiated by a Taipei artist and researcher Rikey Cheng.

40 — Rancière. The Night of Labor.

41 — Margareta, “Cahaya untuk penaku”.

42 — Thea, Epha. 2016. op.cit.

43 — On the book cover, the title is written in Cambodian, Viet and Tagalog. The book presents each piece of writing in its original language. This means the book cannot be accessed by those not able to read the languages used by the authors.

44 — Nara, Aiyu. “Tukang Pos & Surat Kecil Untuk Ibu” (A mail man and a little 44. letter for Mother). In Cahaya. Taipei: Taiwan Literature Award for Migrants. 2017. p. 114.

45 — Wulansari, Rahayu. “Rindu di semangkuk sup kelereng merah” (A sense of longing in a bowl of red marbles soup). In Cahaya, p. 83.

46 — Sadik, Safitrie. “Chau dan perahu naga” (Chau and the dragon boat). In Cahaya, pp. 116-143.

47 — Ibid., p.42.

48 — Sirius, Riris. “Kaki pengganti” (The Substitute Leg). In Cahaya, p. 162.

49 — Diallova, Etty. “Merah.” In Cahaya, pp. 192-213.

50 — Ibid., p. 209.

51 — Devi, Arista. Kesaksian Ungu: Empat Musim Bauhinia Ungu (Four Seasons of Purple Bauhinia). Yogyakarta: LeutikaPrio. 2012.

52 — “Arggh! Aku ingin berteriak, berita yang tertulis itu salah! Kenapa mereka tak menuliskan sebab terjadinya kecelakaan itu karena perempuan itu melamun, ia sedang terluka batinnya. Majikan perempuan telah menyiksanya dan majikan laki-lakinya sudah memperlakukannya dengan tidak senonoh. Dan perempuan itu hanya punya aku, hanya aku. Seharusnya mereka meminta kesaksianku karena aku tahu semuanya. Ia selalu mengadukan semua perbuatan buruk yang diterimanya padaku. Aku bersedia bersaksi! Aku mau majikan jahat itu dihukum karena telah menyebabkan kematian seseorang yang tak bersalah. Panas. Tubuhku tiba-tiba terasa panas, seperti aku terbakar amarahku sendiri. Kudapati satu-persatu bagian dari tubuhku perlahan mengabu. Aku meronta. Ternyata api yang menyala dalam tungku pembakaran sampah itu akan segera melahap habis tubuhku. Aku tak boleh mati sebelum memberikan kesaksianku. Ya, Tuhan, tolong aku… Pada detik-detik terakhir ini kenapa aku baru ingat siapa sebenarnya aku. Ternyata, aku ini hanya sebuah buku, buku diary yang berwarna ungu.”

53 — Taussig, Michael. I Swear I Saw This: Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, Namely My Own. Chicago, IL, and London: The University of Chicago Press. 2011.

54 — Ibid. p. 111.

55 — Margareta, , “Cahaya untuk penaku”.

56 — Walden, Max. “Hong Kong protest reporter, Indonesian citizen Yuli Riswati, deported after detention”. ABC News. 9 December 2019. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-09/hong-kong-protest-reporter-yuli-riswati-deported/11669194 (accessed 2020-05-06).